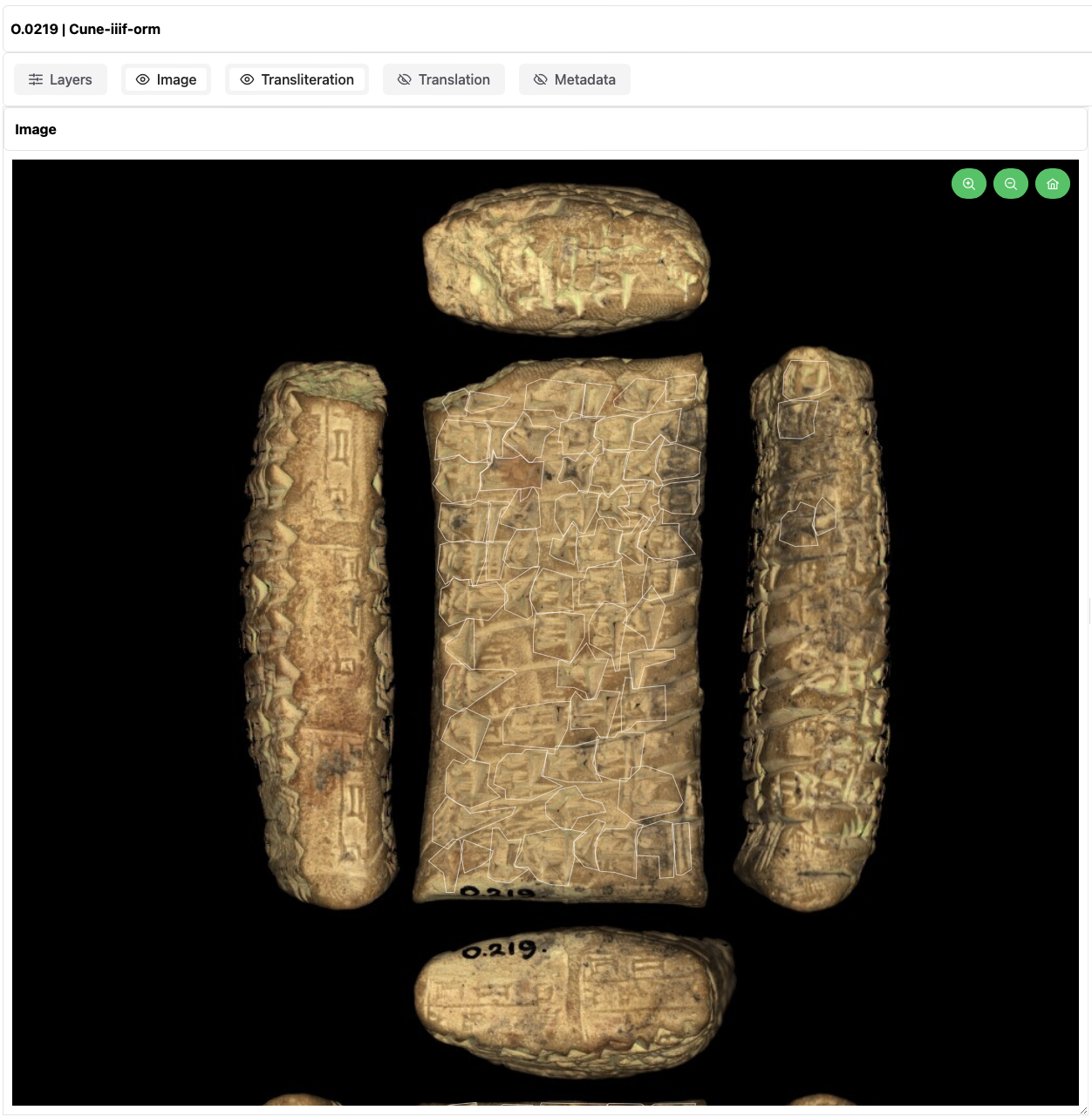

The Royal Museums of Art and History (RMAH) collection holds several Cuneiform Tablets that have been digitized by KULeuven Libraries’ Digitisation and Document Delivery department and its Imaging Lab. The Cuneiform Tablets have been digitized using a Portable Light Dome, taking pictures from a single camera viewpoint but with multiple light angles. With the resulting reflection data, a depth map of the tablet surface can be constructed. The finale image format Pixel+ allows researchers to study the tablets by moving a virtual camera over the object. Because the Pixel Plus format generates several gigabytes of data for each image however, the original scans cannot feasibly be published on the web due to the long loading times.

We explore the potential of a digital scholarly edition of cuneiform tablets as an exhibition. By integrating curation into our process, we aspire to enhance both the attractiveness and usability of the digital scholarly edition. We want to ensure that the digital scholarly edition encompasses (1) all the essential components, information, and data required by Assyriologists for the study of cuneiform tablets, and (2) the optimal user experience.

Firstly, we gathered and modelled extensive data. Secondly, we identified the specific needs of Assyriologists and determined the requirements of a digital scholarly edition. The design process started from assessing the needs of Assyriologists in a focus group where they explained their research process to create a digital scholarly edition in depth. They evaluated four other applications and their pros and cons. We created a prototype based on an initial focus group to assess the needs of Assyriologists. The developers then created the web interfaced based on Lise Foket's prototype.

Focus Group

- by Lise Foket

The focus group of Assyriologists held on April 24, 2024 with Prof. Dr. Katrien De Graef, Gustav Ryberg Smidt, and Mirko Surdi reviewed four interfaces: mmmonk, SATDB2018, READ Latin, and PRISMS. mmmonk received praise for its layers toggle, pinning of an annotation, simplicity of the interface and ease of use. The display of annotations was considered outdated and mmmonk lacked zoomable images. Overall the interface leaned towards a virtual exhibition rather than a thorough scholarly edition. SAT DB 2018 instead had so many functionalities that it hindered the use. So while Assyriologists liked the workbench format with two windows split into the image on the left and text on the right, the buttons and actions were too confusing. Other positive feedback for SATDB2018 were the multiple export functions and the functionality to increase or decrease the brightness and contrast of the IIIF viewer. READ Latin also looked outdated and they bumped into bugs in the interface. While the goal of the interface was quite simplistic, the tool succeeded. Interaction between image and text worked both ways, and the grammatical annotation overlay over the text was appreciated by the focus group. PRISMS was not as user-friendly and did not link between image and text. There were quite a few pros to the interface however: the zoomability of IIIF, a workbench plug format with multiple boxes to show and hide various levels of annotations, grammatical annotations above regular text layers and a sort of shopping basked were all appreciated by Assyriologists.

In terms of viewer experience, the deep zoom is a minimum requirement for image and layers. IIIF includes an excellent deep zoom to study the signs on Cuneiform tablets in detail. A variety of image layers and ideally the increase and decrease option of brightness and contrast allows Assyriologists to study the signs up close. Metadata needs to be easily visible and accessible to determine which tablet from which collection is displayed but should also be hidden afterwards. This option is included in the Mirador viewer for IIIF. Assyriologists work on three levels of annotations: transliteration, translation, and material. Ideally these levels are clickable and visible in a separate box next to the image, like in the PRISMS interface. Mirador’s display of basic annotations in the style of a list did not suffice. Two other requirements emerged from the focus group. Assyriologists wanted to highlight named entities such as people and location with a clickable link to find other tablets containing the same named entity. Grammatical annotations should be visible on top of the transliteration to easily ask for explanation of unclear pieces of information.

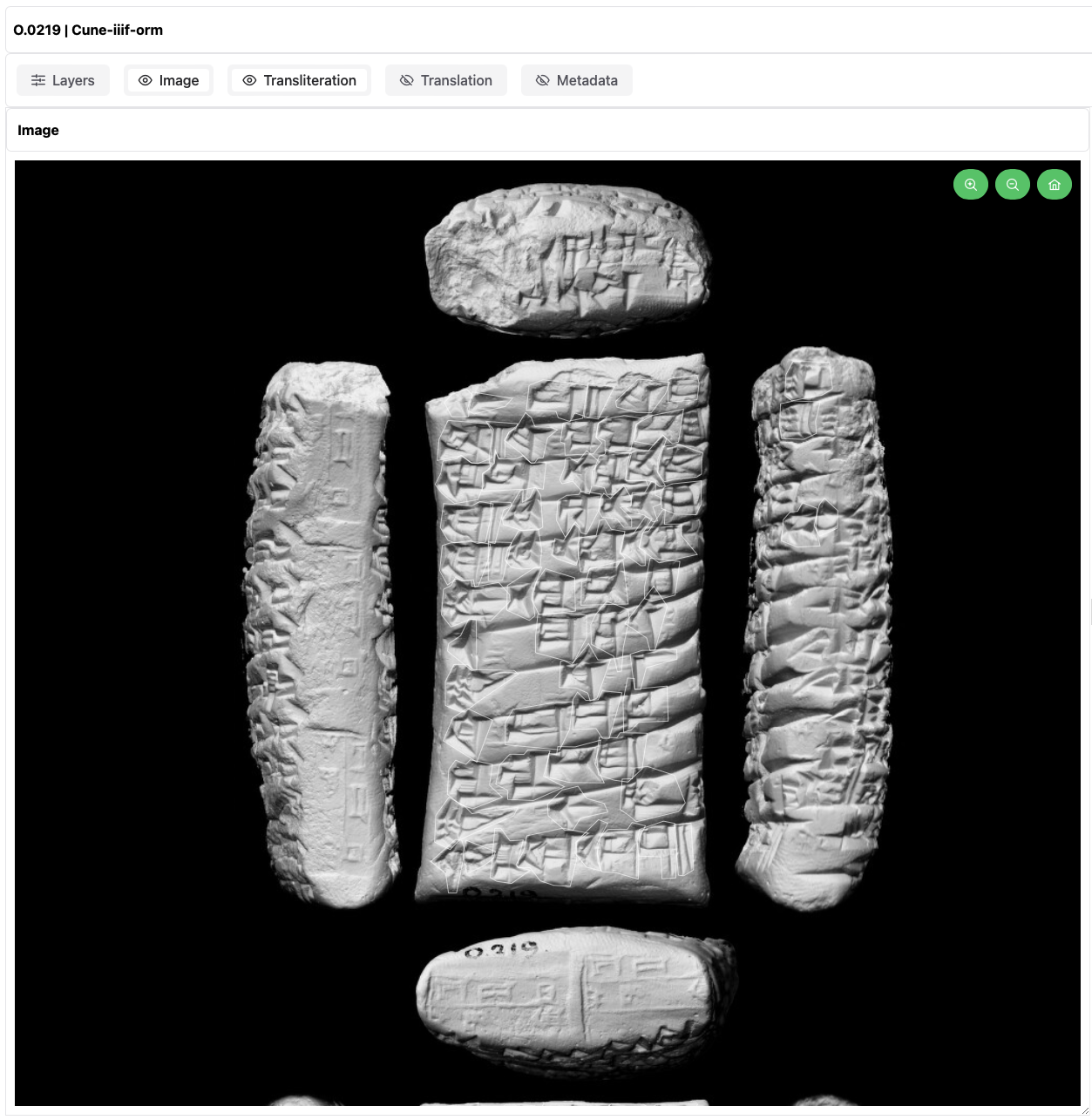

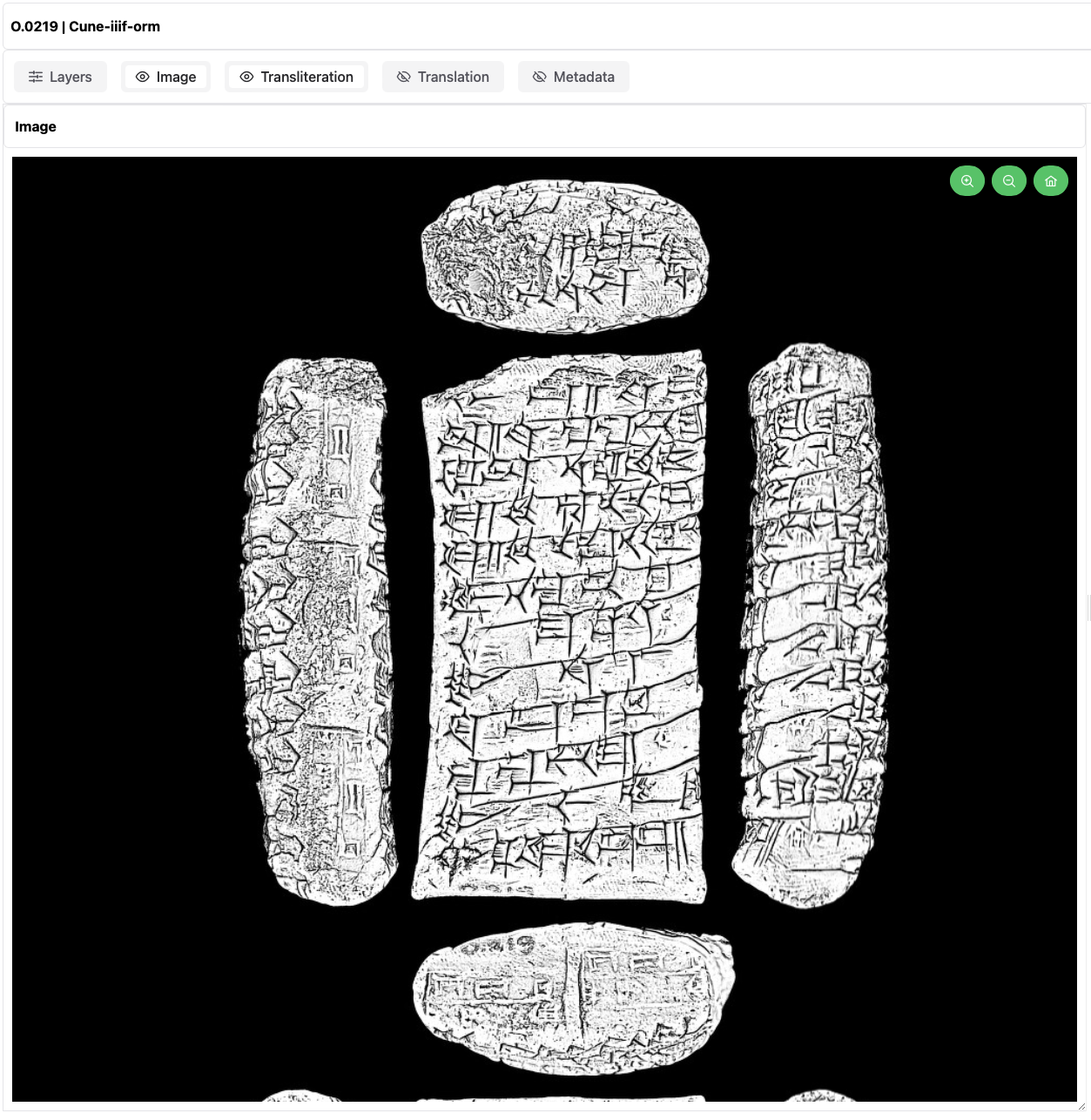

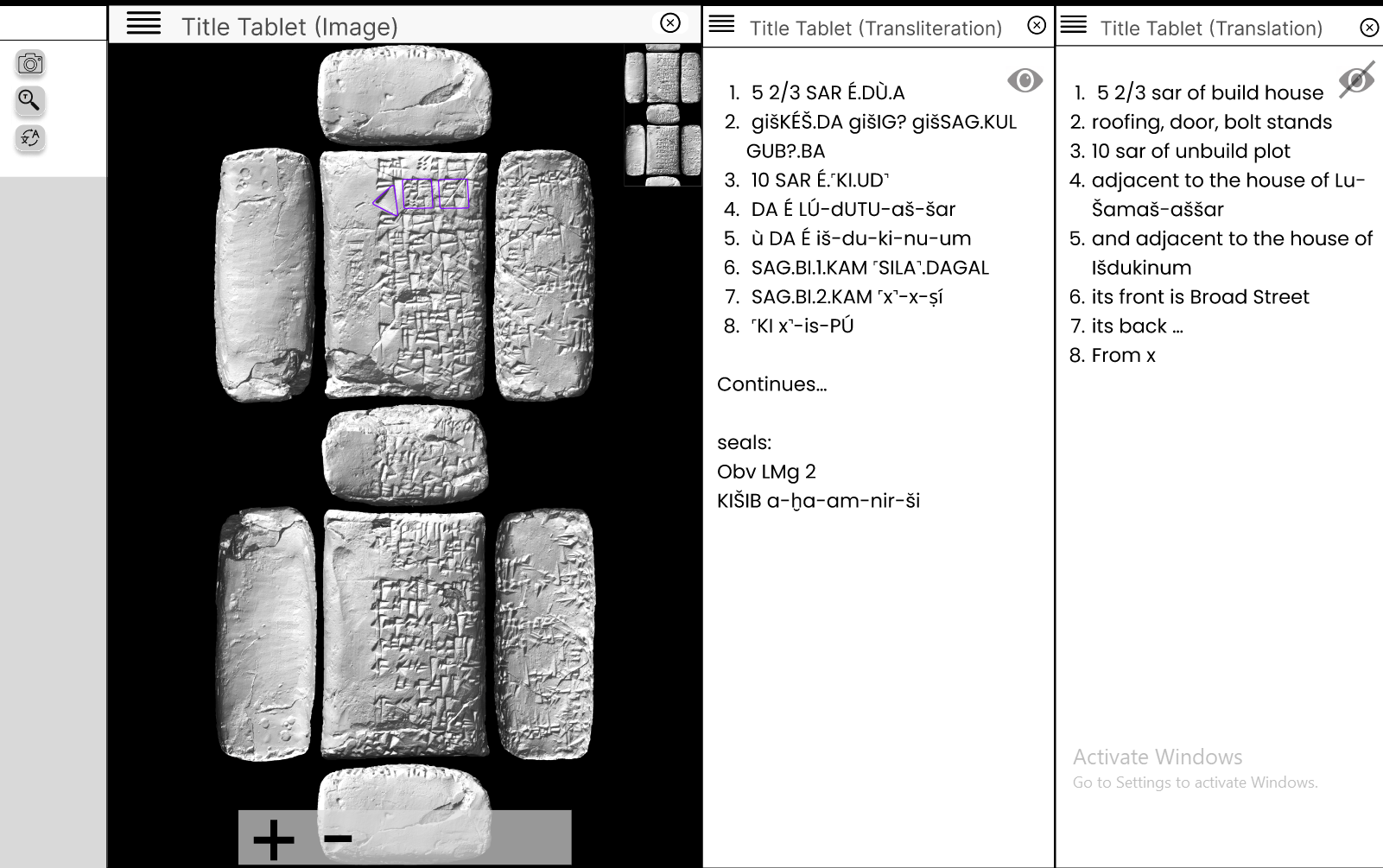

Experimenting with Depth

Our developers, Frederic Lamsens and Joren Six, have worked tirelessly to create a web interface enabling researchers to study the Cuneiform Tablets in detail. First, the Digitisation and Document Delivery department has selected a limited number of camera angles, colours, and luminosities to view all sides of a single Cuneiform Tablet in one image. By adjusting the transparency, researchers can simulate different lighting angles and create a sense of depth without a proper 3D image. The greyscale image view for instance creates an even better sense of depth. Postprocessing in Sketch has made the signs on the Cuneiform tablets even clearer to support Optical Character Recognition (OCR).

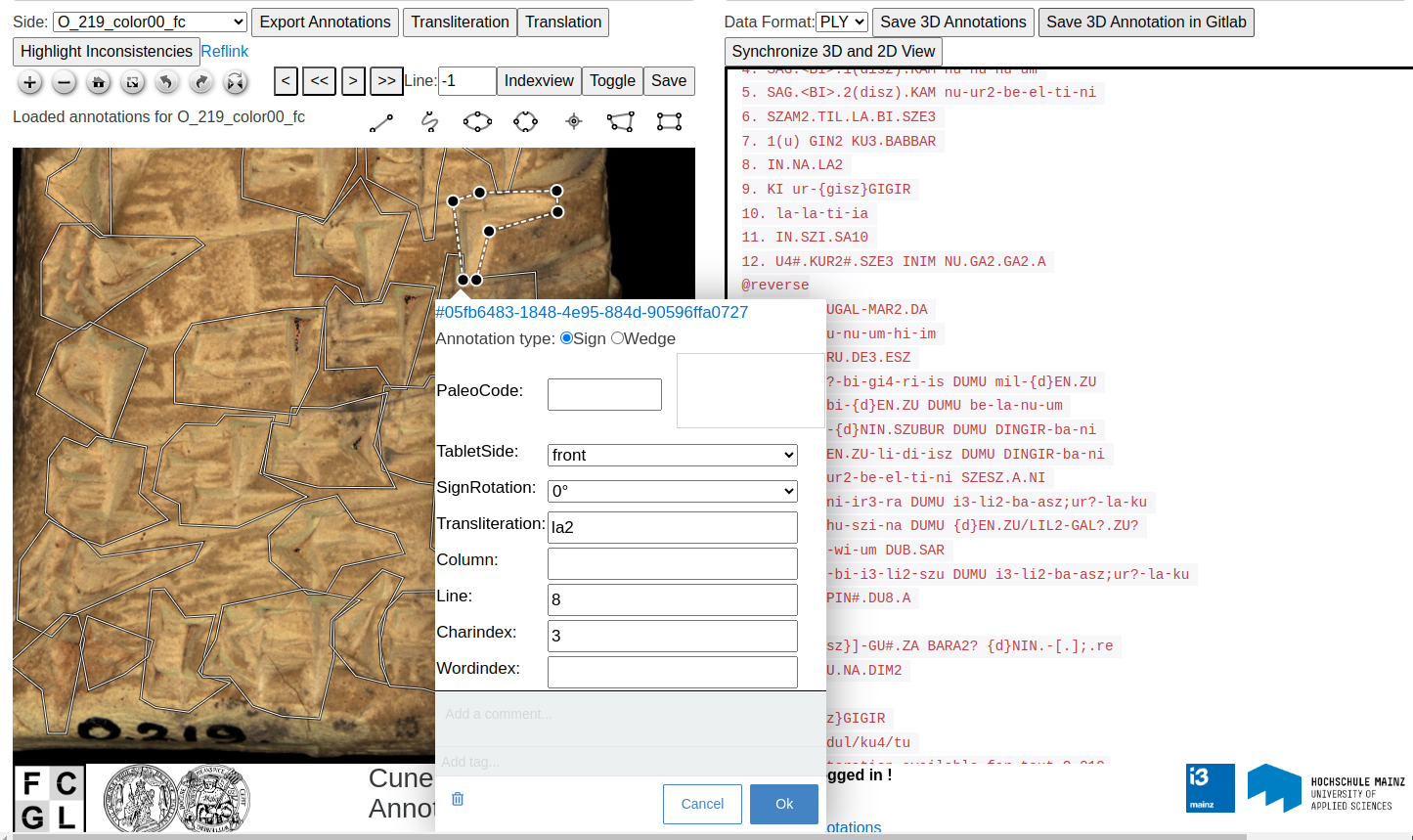

Annotation and Transliteration

An annotation platform developed by i3mainz – Institut für Raumbezogene Informations- und Messtechnik at Hochschule Mainz in Germany allows researchers to select, annotate, and transliterate each individual sign on the Cuneiform Tablets while keeping track of its character- and line position. The resulting W3C annotations can be used to construct an ATF document that describes the type of object, which side of the tablet has been transliterated, followed by the transliteration including a word and character index. In other words, the data provides a full mapping of where each sign is positioned on the Cuneiform Tablet.

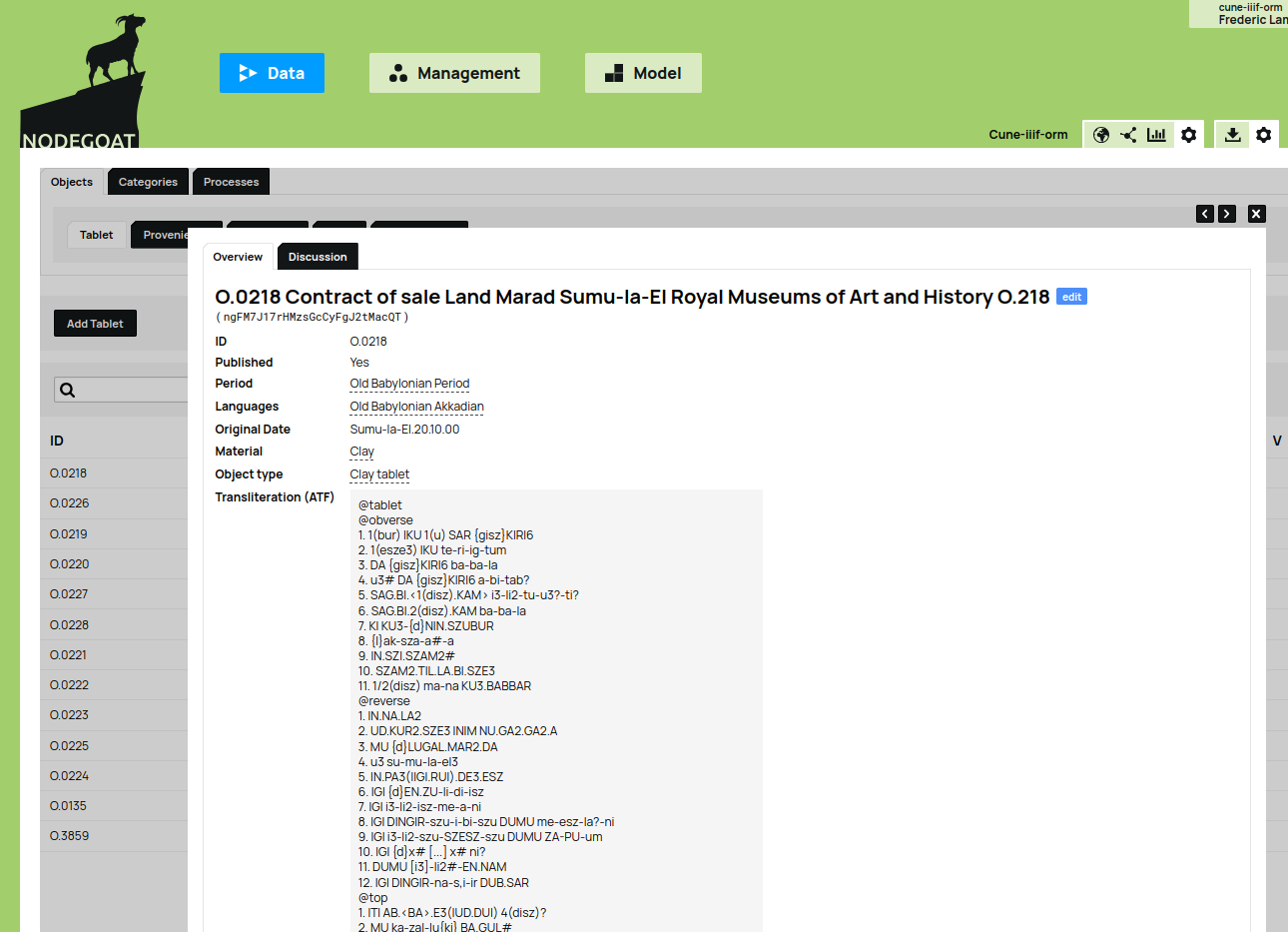

Gathering Metadata, Transliteration, and Translation

To gather all data concerning each tablet, including metadata, transliteration and translation we have set up a NodeGoat[https://nodegoat.net] database for researchers. For each tablet the database includes metadata such as: the type of tablet, the period, language, material, date, transliteration, genre of the text, provenience , the ruler in power at the time, and external IDs to where the Cuneiform Tablet is published and in which collection. All properties listed here link to a FactGrid instance, or a WikiData instance that cannot erase any data. For instance, all genres such as letters, payments, demands, etcetera, are all linked to a FactGrid item. A FactGrid allows us to export the Cuneiform data as Linked Open Data at a later stage, because properties are limited to those described in the FactGrid.

Web Application

The web application developed by GhentCDH glues all the data together, metadata linking to the FactGrid, the translation, the Cuneiform Tablet with all annotations, the layers where we can change transparency. By hovering over lines, words, or signs, the relevant location on the tablet will be highlighted on the image of the tablet. The goal of the demo was to show how we can display all the information gathered for a single Cuneiform Tablet.

This test application was developed for a conference presentation by Gustav Ryberg Smidt, but the development of the web application is more advanced. The Cuneiform Tablets have been digitized, and researchers are continuously working on the annotations and collection of metadata to eventually create a scholarly edition.

Scholarly Edition

Researchers using the web application can choose from multiple colour and shade layers, highlight the areas of the transliteration on the IIIF image, and display the metadata for each manifest. The toggles at the top will eventually allow researchers to compare either multiple luminosities of the same tablet (colour, grayscale, or sketch) or multiple tablets. In the end we want to create a scholarly edition gathering all information.

Another goal of the CUNE-IIIF-ORM project is to train an OCR model to recognize recurring signs in all images. Krishna Kumar Thirukokaranam Chandrasekar[https://research.flw.ugent.be/en/krishnakumar.tc] will attempt a recognition rate of 70 to 80%, which is high for such a challenging script/language.

Researchers will also be allowed to create their own project environment. The goal is to synchronise two images of the same tablet so that you can compare two different layers for the same Cuneiform Tablet. Another feature that the team will implement is a link for Named Entities in the transliteration to a person or place listed in the FactGrid.

This viewer was custom built, but we eventually want to transform the Cuneiform Tablets into digital equivalents including all information according to the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF)[https://iiif.io]. The end goal is to experiment with exporting all data linked to a tablet into a IIIF-manifest for a museum web viewer.

Museum Web Viewer

We want to be able to export this information to IIIF-manifests. Now we can already see all layers of a Cuneiform Tablet in a IIIF viewer such as Mirador and all individual signs, but these cannot be paired with the relevant word or line in the transliteration. So, while we can code the data into a IIIF-manifest, we cannot display all data in a IIIF viewer. We aim to expand the infrastructure so that the Royal Museum of Art and History (RMAH) can display all information concerning a Cuneiform Tablet via a IIIF manifest that can be hosted on their website or infrastructure. Visitors would then be able to display the Cuneiform Tablet in a standard IIIF viewer without requiring a scholarly edition.

Technical Challenges

The major technical challenge we faced were the data transformations. The data originates from several sources. The transliterations are all W3C annotations, the Cuneiform metadata is stored in NodeGoat where we gather most information. So we need to gather a lot of data in one format to create a search index to facilitate an elastic search and quickly query the data in our web application. Parsing the ATF format is supported by some old Python 2.7 libraries, but very few other languages. Therefore, Joren Six has written a parser in Node.js to link each sign with the annotation on the Cuneiform tablet in a browser environment.

Once we decided on storing the information in a FactGrid, we could simply list the labels and the URIs for all metadata. We decided not to collect most data in our database, but rather refer to web pages where the data can be described extensively in a human- and machine-readable way. If the data is ever published as Linked (Open) Data, we will also be able to parse information from FactGrid. By linking to external sources we have greatly simplified our data model.

Usability in Other Projects

We always aim to publish open-source software, but the tablet viewer and front-end for the demo are still under development. We have documented the ATF-parser, and the manifest builder is publicly visible, but currently missing documentation. By the end of the project the tools will be published in the GitHub repository. We try to avoid hard coding in custom projects and instead write generic and modular code so that we can reuse components in other software. For instance, we can easily and quickly integrate the viewer that allows us to highlight and link to annotations on an image. Aside from the text annotation component, we have written each of the toggles in the web viewer as separate components allowing us to easily add toggles later.

Future Features

Since very few researchers can work with Linked Open Data, we want to be able to export information from the CUNE-IIIF-ORM project in several formats allowing researchers to select the information they want to export. Once more Cuneiform tablets have been prepared by Gustav Ryberg Smidt and added to the web application, we will make them searchable based on all available information including metadata, transliteration, translations and even named entities. Researchers can then export the list of results from a search, or simply select several tablets from their personal project and export the data. A nice-to-have feature would allow other researchers to add annotations to the data already present within this project.